Cyrix: Gone But Not Forgotten

Most of you are no doubt familiar with Intel and AMD, Qualcomm, Texas Instruments, and possibly fifty-fifty VIA -- simply at that place's another forerunner bit maker that you should be familiar with. For the better function of a decade, Cyrix brought the world of personal calculating to millions in the form of attainable upkeep PCs, just to be killed by its best product and its disability to run a popular game, followed by a bad merger with a larger partner.

The early 1990s were a strange fourth dimension for the desktop computing manufacture. It looked like Intel was winning despite trigger-happy competition in the microprocessor space -- Apple tree switched to IBM PowerPC, while Motorola'south 68K chips were slowly dragging Commodore's Amiga PC to the grave. Arm was only a tiny flame sparked by Apple and a few others, and was almost entirely focused on developing a processor for the infamous Newton.

This was around the same time AMD was liberating its processors from the negative aura of being 2nd-sourced from Intel. Later cloning a few more generations of Intel CPUs, AMD came up with its ain architecture, which by the end of the nineties were well regarded in terms of price and functioning.

That success can be attributed at least in part to Cyrix, a company that had a window of opportunity to capture the home PC market and get out both Intel and AMD in the grit, only ultimately failed to execute and quickly disappeared into the tech graveyard.

Pocket-sized Beginnings

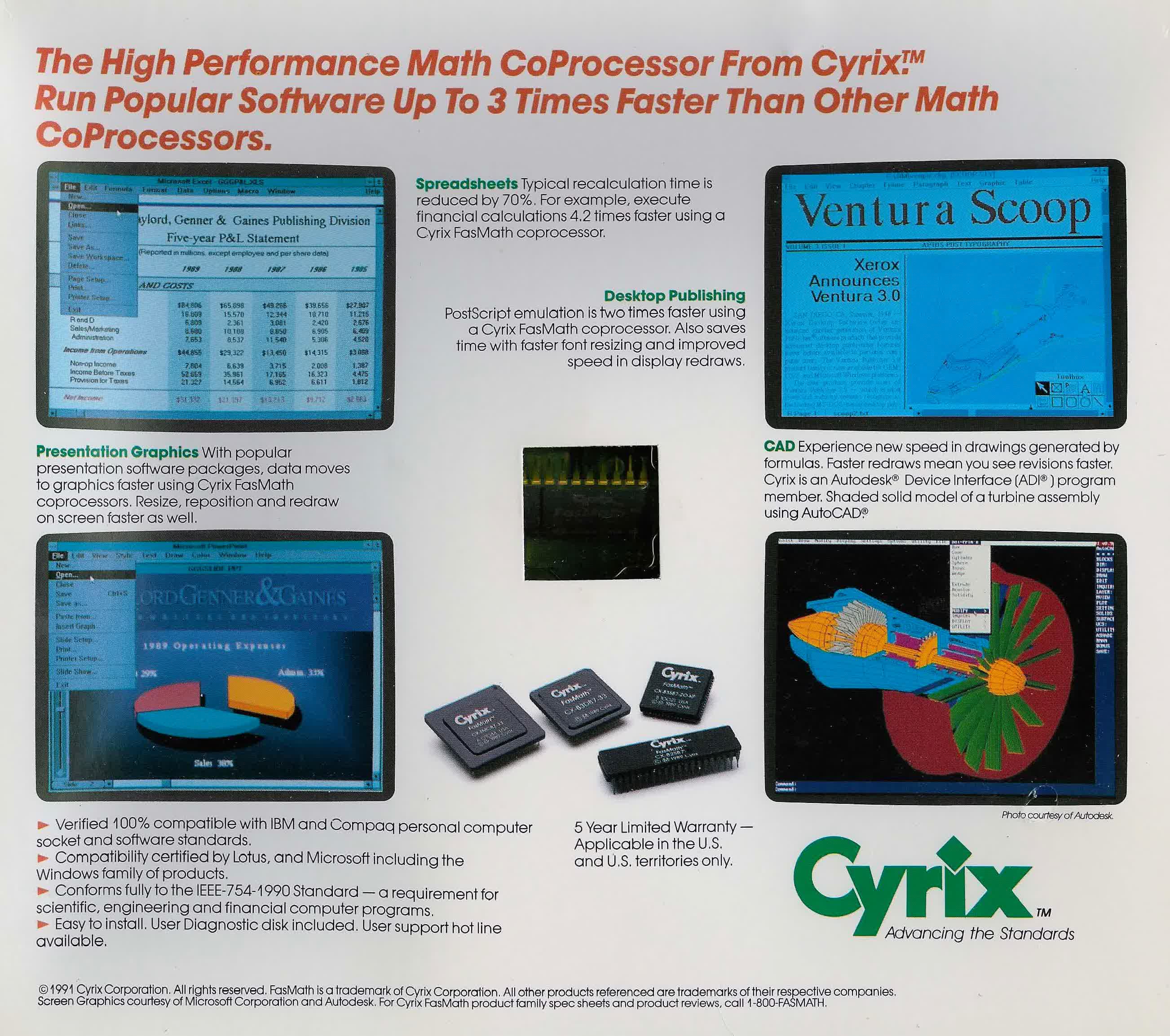

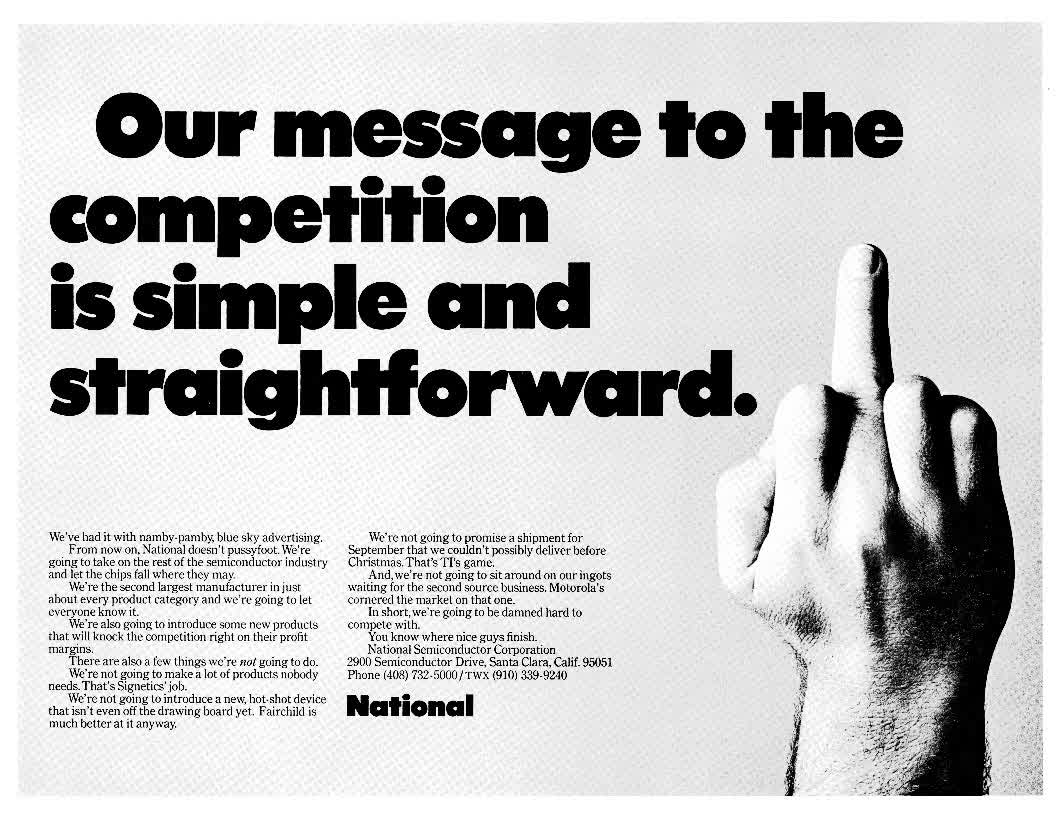

Cyrix was founded in 1988 by Jerry Rogers and Tom Brightman, starting out every bit a manufacturer of high-speed x87 math co-processors for 286 and 386 CPUs. These were some of the greatest minds to get out Texas Instruments and they had high ambitions to take on Intel and beat out them at their own game.

Rogers embarked on an aggressive pursuit to detect the best engineers in the U.s.a. and proceeded to become an infamously hard-driving leader for a team of thirty people that were tasked with the incommunicable.

The company's showtime math coprocessors outperformed Intel equivalents past ~fifty% while as well beingness less expensive. This fabricated it possible to pair an AMD 386 CPU and a Cyrix FastMath co-processor and go 486-similar performance at a lower price, which caught the industry's attention and encouraged Rogers to accept the next step and pursue the CPU market place.

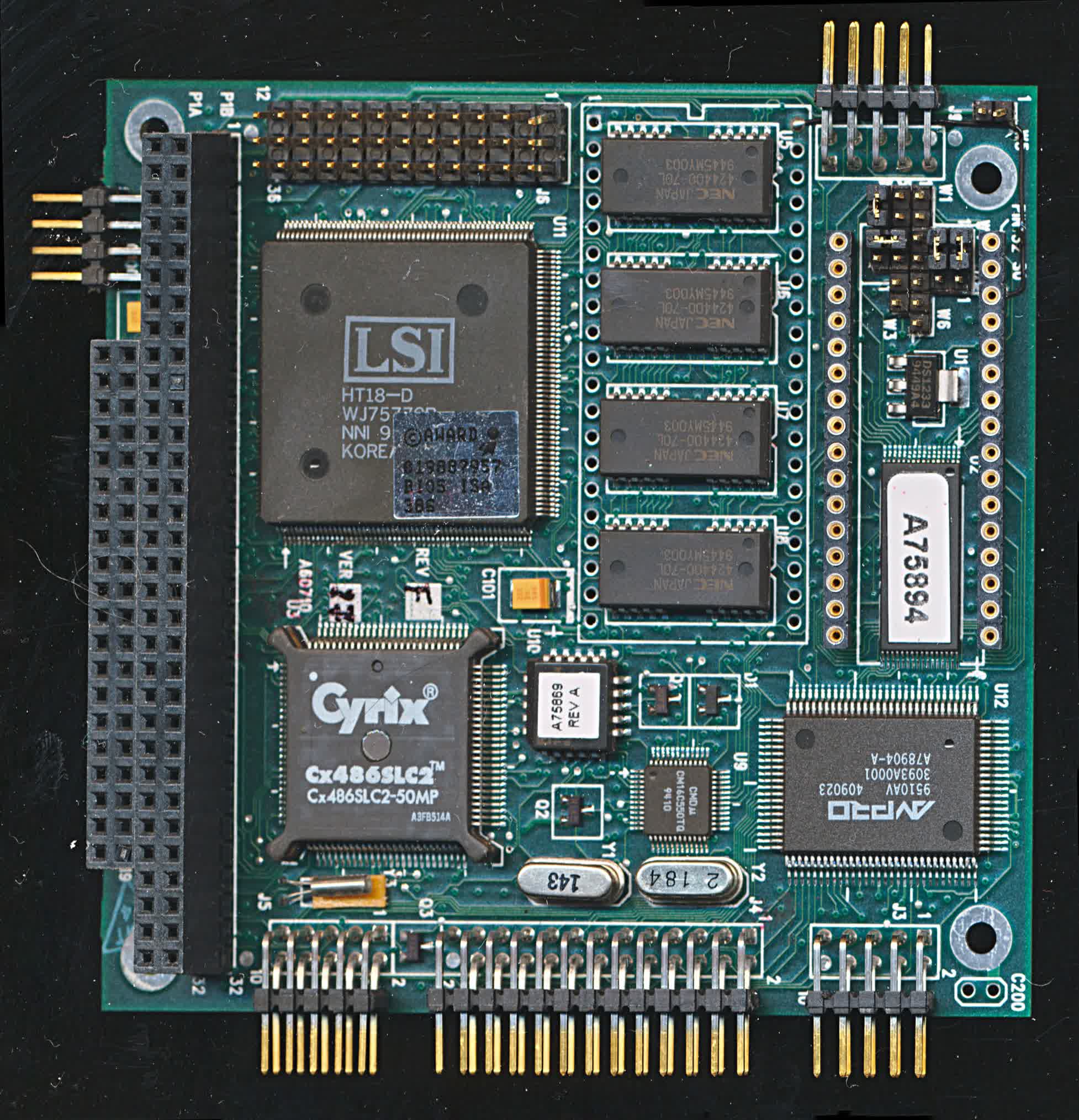

In 1992, Cyrix unveiled its first CPUs, the 486SLC and 486DLC, which were intended to compete with Intel'southward 486SX and 486DX. They were also pin-compatible with the 386SX and 386DX, meaning they could exist used equally drib-in upgrades on ageing 386 motherboards, and manufacturers were too using them to sell upkeep laptops.

Both variants offered slightly worse performance that an Intel 486 CPU but significantly improve performance than a 386 CPU. The Cyrix 486 DLC wasn't able to compete with Intel's 486SX offering clock-by-clock, but it was a fully 32-bit chip and sported 1KB of L1 cache, while costing significantly less.

At the time, enthusiasts loved the fact that they could apply a 486DLC which ran at 33 Mhz to accomplish comparable functioning to that of an Intel 486SX running at 25 MHz. That said, it wasn't without bug, every bit information technology could lead to stability bug for some older motherboards that didn't take extra cache control lines or a CPU register command to enable or disable the on-board cache.

Cyrix likewise adult a "direct replacement" variant called Cx486DRu2, and later on in 1994 released a "clock doubled" version called Cx486DRx2, which had the cache coherency circuitry integrated into the CPU itself.

By then, however, Intel had released its first Pentium CPU, which drove 486DX2 prices down to the point where the Cyrix culling had lost its entreatment every bit information technology was cheaper to upgrade to a 486 motherboard than it was to buy a Cyrix upgrade processor for an old 386 motherboard. When the "clock tripled" 486DX4 arrived in 1995, information technology was likewise little, as well tardily.

Large PC manufacturers such as Acer and Compaq weren't convinced by Cyrix's 486 CPUs and instead opted for AMD's 486 processors. This notwithstanding didn't stop Intel from spending years in court alleging that Cx486 violated its patents, without ever winning a instance.

Cyrix and Intel eventually settled outside of court and the latter agreed that Cyrix had the right to manufacture its own x86 designs in foundries that happened to hold an Intel cross-license, such as Texas Instruments, IBM, and SGS Thomson (later STMicroelectronics).

Never Repeat the Same Flim-flam Twice… Unless Yous Are Cyrix

Intel launched the Pentium processor in 1993, based on a new P5 microarchitecture and finally coming up with a marketplace-friendly proper name. But more importantly, it raised the bar in terms of performance that ushered in a new era of personal computing. The novel superscalar compages allowed it to complete two instructions per clock, a 64-flake external information coach made it possible to read and write more information on each memory admission, the faster floating signal unit of measurement was capable of upward to 15 times the throughput of the 486 FPU, and several other niceties.

Cyrix took on the challenge to yet again create a middle ground for Socket three motherboards that were not able to handle the new Pentium CPU, before that model was even ready to ship. That middle ground was the Cyrix 5x86, which at 75 MHz offered many of the features of fifth-generation processors similar the Pentium and AMD's K5.

The company even made 100 MHz and 133 MHz versions, but they didn't actually have all the advertised performance-enhancing features since they would cause instability if enabled, and overclocking potential was limited. All of these were brusk-lived and in six months Cyrix decided to stop selling them and moved on to a different processor design.

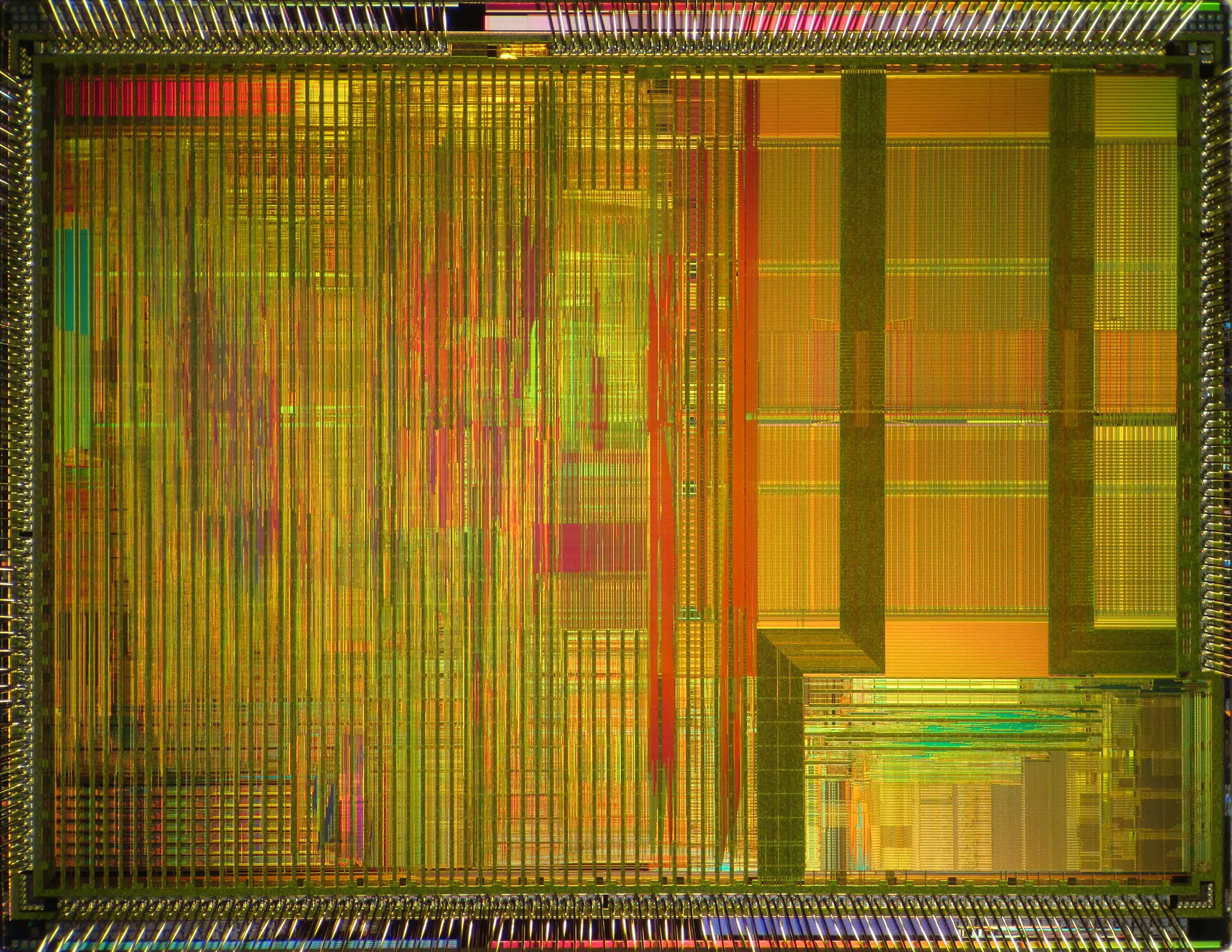

Elevation Cyrix Through the Lens of Quake

In 1996, Cyrix unveiled the 6x86 (M1) processor, which was expected to be yet another drop-in replacement for older Intel CPUs on Socket 5 and Socket seven motherboards with decent operation. But this wasn't just an upgrade path for upkeep systems, it was actually a piddling marvel in CPU blueprint that was idea to exercise the impossible — it combined a RISC cadre with many of the design aspects of a CISC ane. At the same time, it continued to use native x86 execution and ordinary microcode, while Intel's Pentium Pro and the AMD K5 relied on dynamic translation to micro-operations.

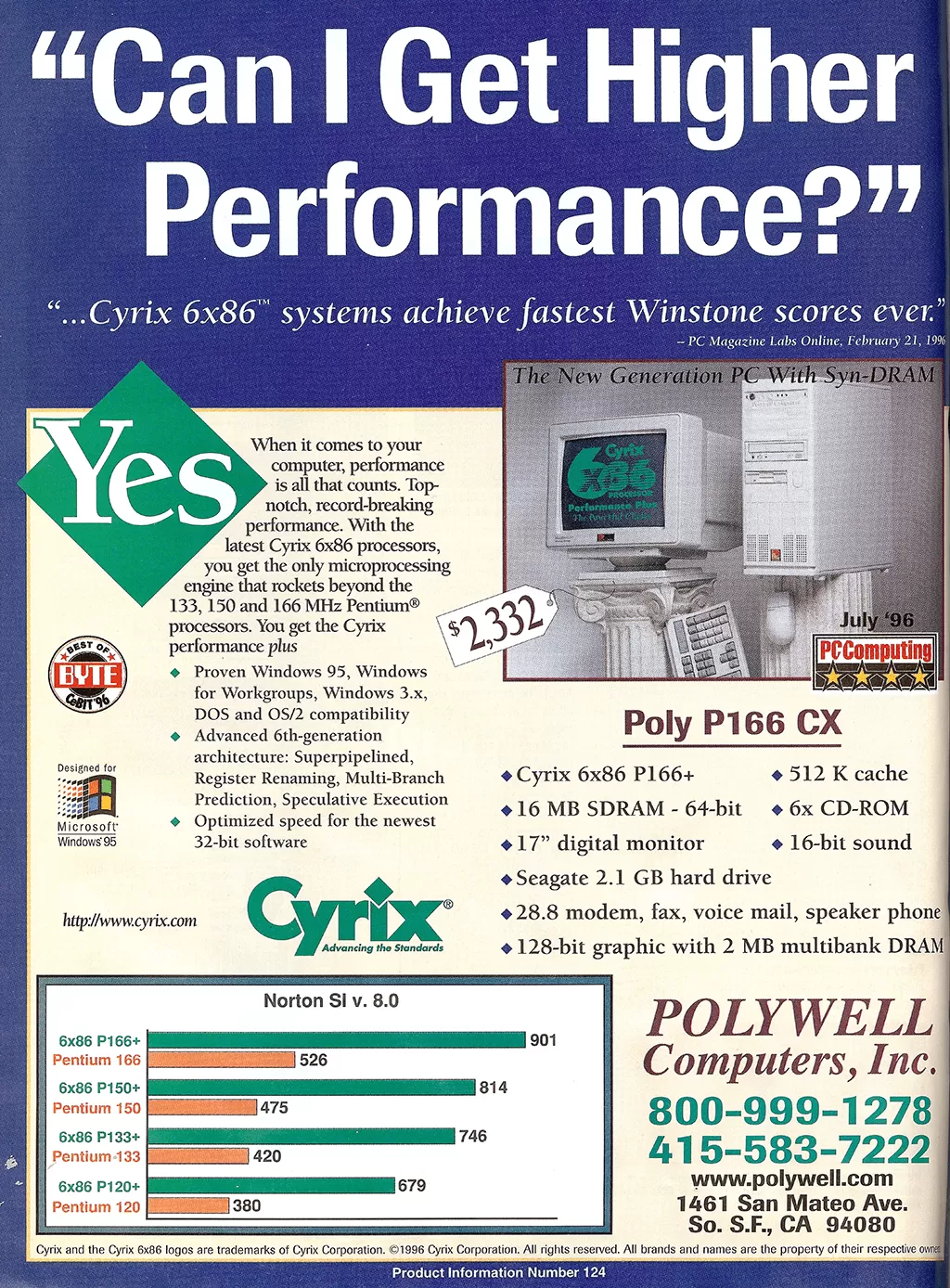

The Cyrix 6x86 was pin-compatible with the Intel P54C and had six variants with a confusing naming scheme that was supposed to point the expected performance level, only wasn't an bodily indicator of clock speed.

For instance, the 6x86 PR166+ simply ran at 133 MHz, and was marketed as being equivalent to or better than a Pentium running at 166 MHz, a strategy that AMD would replicate later on.

Be that as it may, the problem was that the 6x86 really identified itself as a 486 CPU considering it didn't back up the total Intel P5 instruction fix. This would quickly become an issue as most application development was slowly migrating towards P5 Pentium-specific optimizations to squeeze more performance using the new instructions. Cyrix somewhen improved compatibility with the Pentium and Pentium Pro through the 6x86MX and 6x86MII variants.

A huge selling indicate of the 6x86 was that its integer performance was significantly better than the Pentium's, which was a good advantage to have at a time when the vast majority of applications and games relied on integer operations. For a while, Cyrix even tried to charge a premium for that added operation, only eventually that strategy roughshod apart.

As information technology turned out, the FPU (floating betoken unit) of the 6x86 was only a slightly modified version of Cyrix'due south 80387 coprocessor, and equally such, significantly slower than the new FPU design integrated by Intel's Pentium and Pentium Pro.

To be fair, it was still anywhere between two and four times faster than the Intel 80486 FPU, and the Cyrix 6x86 bested the Intel offerings on overall functioning. But that whole equation bankrupt down when software developers, particularly those making 3D games, saw the rising popularity of the Pentium and chose to optimize their code in assembly linguistic communication around the advantages of the P5 FPU.

When id Software released Quake in 1996, PC gamers using 6x86 processors discovered they were getting sub-par frame rates that reached at nigh, an unplayable fifteen frames per second, unless they wanted to driblet the resolution down to 320 by 200, in which example you'd take needed a elevation of the line, Cyrix 6x86MX PR2/200 CPU to get a playable 29.seven frames per 2d. Meanwhile, gamers with Intel systems had no problem running the game at playable frame rates even at 640 by 480.

John Carmack had figured out that he could overlap integer and floating point operations on Pentium chips, as they used unlike parts of the P5 core for everything except instruction loading. That technique didn't piece of work on the Cyrix core, which exposed the weakness of its FPU. Reviewers at the fourth dimension plant that in every other benchmark or performance test, the 6x86 CPU would leapfrog the Pentium past xxx to forty percentage.

Back in the mid 90s, no one knew the exact direction that calculating would accept, and Cyrix thought it was best to prioritize integer performance, so information technology produced a processor that lacked teaching pipelining, a characteristic that would become an essential function of a desktop CPU. Pedagogy pipelining is a technique that divides tasks into a gear up of smaller operations that are then executed by different parts of the processor simultaneously, in a more efficient way. The FPU of the Pentium processor was pipelined, leading to a very low latency for floating point calculations to handle the graphics of Convulse.

The trouble was easy to solve and software developers have released patches for their applications and games. But id Software had spent too much time designing Quake around the P5 microarchitecture and never provided such a ready. AMD's K5 and K6 CPUs fared a little meliorate than Cyrix'due south, but they were still inferior than Intel'southward offerings when it came to Convulse, which was a really popular game and a flagship among a new breed of 3D titles.

This had Cyrix CPUs condign harshly judged on that performance gap, and the company all but lost brownie in the eyes of many enthusiasts. Because the company had been unable to score contracts with large PC OEMs, it was a particularly hard accident for Cyrix's fierce customer base of operations that was made up of those same enthusiasts.

To brand matters worse, Cyrix was a fabless bit maker that relied on 3rd parties to industry its processors, and those companies used their nigh avant-garde lines for their own products. Every bit a issue, Cyrix processors were manufactured on a 600 nm procedure node while Intel'southward were 300 nm.

Efficiency suffered, and this is also why Cyrix CPUs had a reputation for getting extremely hot -- so much so that enthusiasts were designing hotplates using them as a oestrus element. They were overly sensitive to depression-quality ability supplies, and their overclocking potential was also limited, simply that didn't stop people (similar this author, whose second PC had a Cyrix 6x86-P166+ CPU inside) from pushing them just a little bit and slowly leading them to their demise.

The Autumn of the Commencement True Rival to Intel's CPU Hegemony

By 1997, Cyrix had tried everything in their power to forge a partnership with companies like Compaq and HP, as integrating its CPUs into their systems would accept generated a steady income stream. Information technology also tried suing Intel for violating its patents on ability management and register renaming techniques, but the matter was settled apace with a mutual cross-license agreement, so that the two firms could stay focused on producing meliorate CPUs.

The litigation took a toll on the already cash-strapped company. Faced with the prospect of bankruptcy, Cyrix agreed to be merged into National Semiconductor. This was seen as a blessing. The visitor would finally have access to proper manufacturing plants and a strong marketing team that was able to score large contracts. The IBM manufacturing agreements held on for a while, but Cyrix eventually moved all production to National Semiconductor.

Even so equally it turns out this movement would seal Cyrix's fate. National Semiconductor wasn't interested in making loftier performance PC parts, and instead wanted low-power SoCs (organization on a chip).

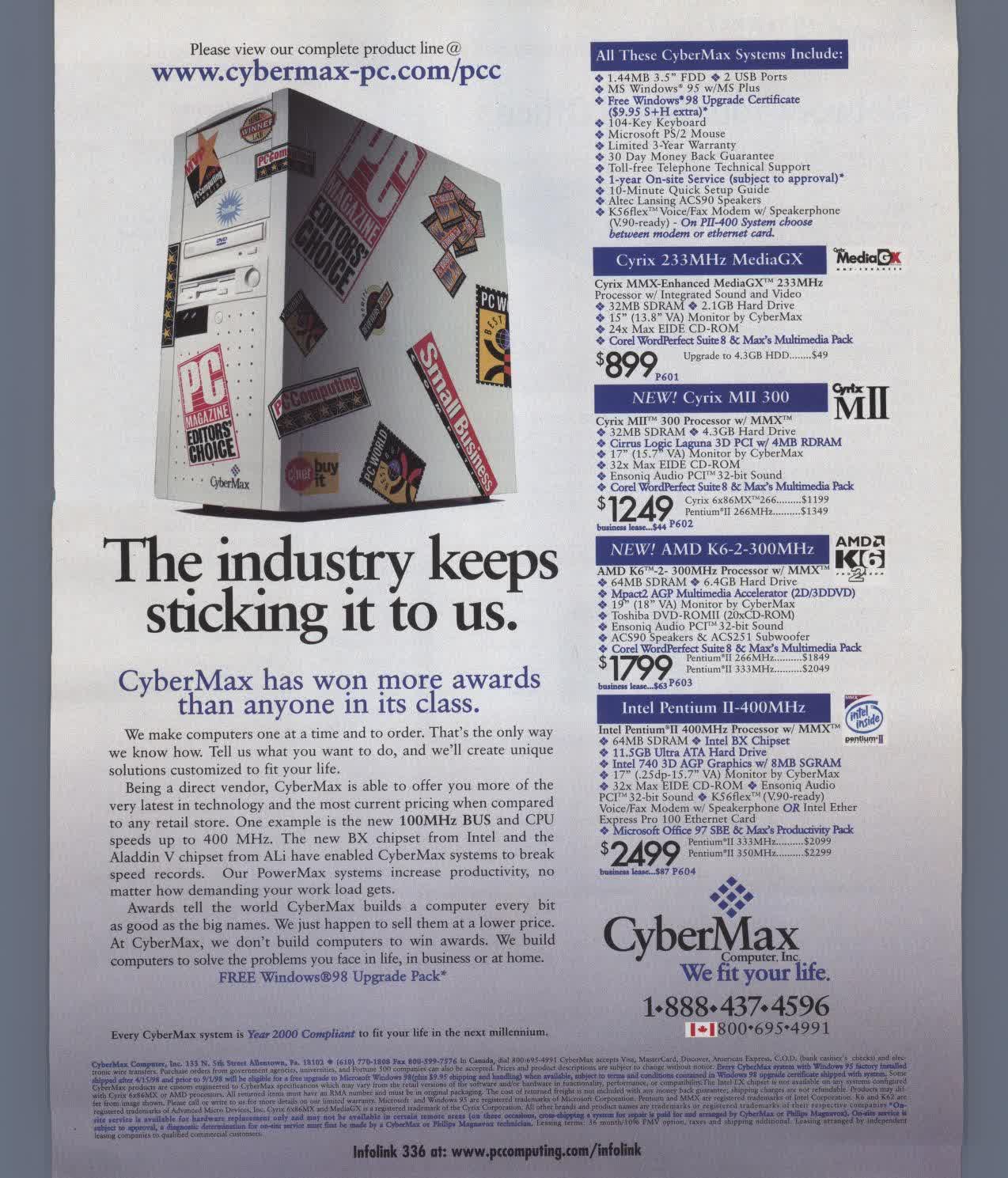

Certain enough, Cyrix came up with the universally-hated 5x86 MediaGX, a fleck that integrated functions like audio, video, and memory controller with a 5x86 cadre running at 120 or 133 MHz. It was a low performer, but it managed to convince Compaq to use it in their low-terminate Presario computers. This whet other OEM's appetite for 6x86 CPUs, with Packard Bong and eMachines as notable examples.

The shift in focus didn't stop Cyrix from trying to produce more high-performance CPUs, but it delivered promises and picayune else. National Semiconductor eventually sold Cyrix to Taiwan-based chipset maker VIA Technologies, but by then key people had already left and the MII CPU was an uninteresting part that establish no buyers.

The concluding Cyrix design was the MII-433GP which ran at 300 MHz and, thanks to the unfortunate naming scheme, concluded up in comparisons with processors that ran at 433 MHz, which were vastly superior. AMD and Intel were decorated racing to one GHz and across, and it would have 20 more years for Arm to come along and challenge the ii giants in the desktop and server markets -- not to mention totally dominate mobile computing.

VIA put the final boom in the coffin every bit it used the Cyrix name to supervene upon "Centaur" branding on processors that actually used an IDT-designed WinChip3 cadre. National Semiconductor kept selling the MediaGX for a few more years, before rebranding information technology into Geode and selling the pattern to AMD in 2003.

Three years later, AMD demonstrated the world's lowest-power x86-compatible CPU, which took simply 0.9 watts of power and was based on the Geode cadre, a testament to the ingenuity of the Cyrix blueprint team.

Why Cyrix's Legacy Matters

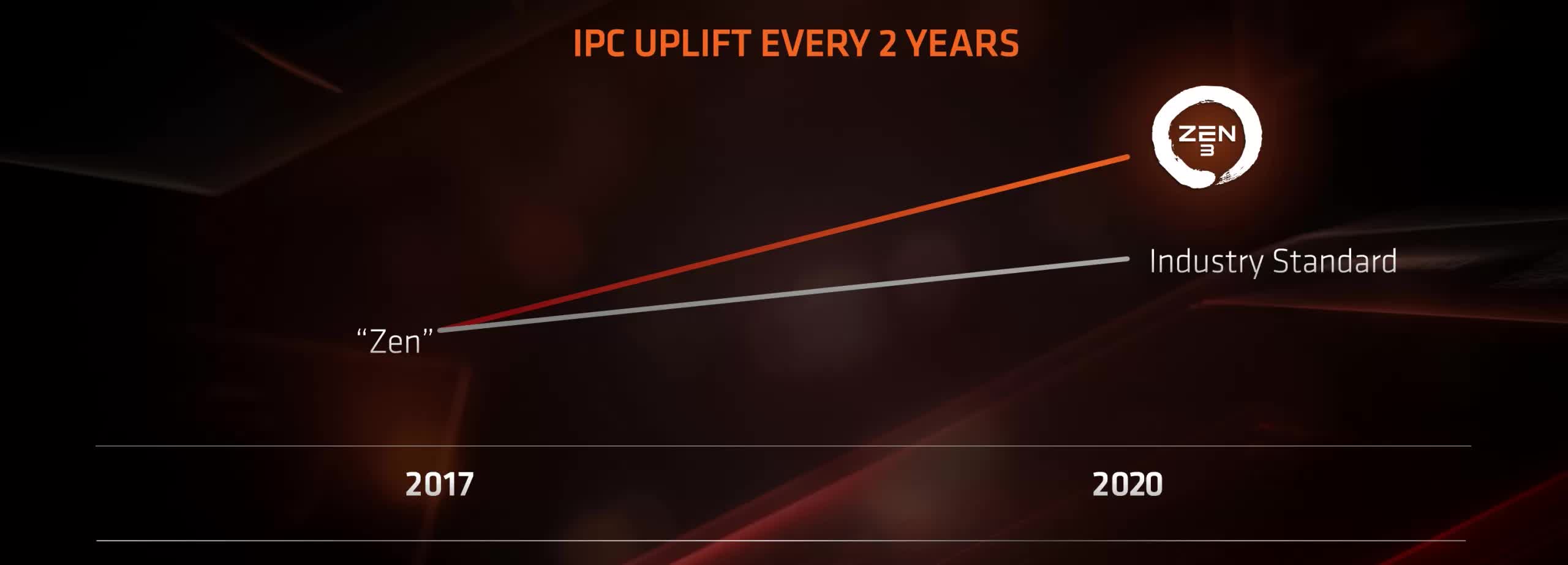

Whether or not you ever endemic a Cyrix-powered PC, the company should be remembered for its legacy and lessons learned. Despite the relatively pocket-size influence on the industry during its decade of existence, Cyrix's failures proved that improving instructions-per-clock (IPC) was a much more productive endeavor for chip makers compared to improving raw clock speeds.

To this day, Intel and AMD take tried to push nominal clock speeds higher with each generation, only after the 3 GHz milestone, near of the real improvements take come from rethinking core parts of their microarchitectures (and caching). A notable instance is AMD'south Zen progression, which has brought single-threaded operation improvements of 68% in less than iv years.

Cyrix was able to survive and overcome a lot of legal (and by extension, financial) pressure from Intel, who sued nigh everyone in the CPU space in the 1990s. It showed on two occasions that litigation is detrimental for a salubrious marketplace while cross-licensing deals lead to a lot of cantankerous-pollination between engineering efforts at unlike companies, which proved benign.

Cyrix also operated as a fabless visitor before that was cool. These days it'due south standard practice for well-nigh silicon giants, including the likes of AMD, Qualcomm, Broadcom, Nvidia, Apple tree, Marvell, Unigroup China, and HiSilicon, who depend on other companies to industry their chips.

The visitor's marketing strategy was never keen before the National Semiconductor merger, and AMD would repeat the aforementioned mistakes with Athlon and Sempron processors in the 2000s. These were labeled every bit to indicate that they were faster than an Intel processor, while operating at a lower clock speed, but that didn't always translate well in benchmarks or existent-world functioning tests. AMD dropped that scheme, merely suffice to say, things remain a scrap confusing to this day.

Today, it's unlikely you lot'll find a Cyrix processor outside of gold reclaiming operations and enthusiasts' vintage figurer collections. There'southward some testify online that Cyrix-based desktops were in use upwardly until at least 2022, meaning they lingered for another decade afterwards the company had essentially dissolved into VIA Technology's soup. It's unlikely that VIA'southward Zhaoxin arm still uses anything coming from the original Cyrix design, but only time will tell if they learned the lessons to honor Cyrix'south legacy.

Image credit: Cyrix 486 dx2 masthead past Henry Mühlpfordt, Cyrix product boxes by CPU Shack.

Source: https://www.techspot.com/article/2120-cyrix/

Posted by: jacksonvoll1986.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Cyrix: Gone But Not Forgotten"

Post a Comment